What’s new?

Brian Armstrong, CEO of San Francisco-headquartered Coinbase, wrote a blog last year that went viral. In it he stated that he wished all employees to be “laser focused” on the company’s mission, that they should not “engage in broader societal issues when they’re unrelated to our core mission” and that employees who wished to be at “an activism-focused” company would be helped to move there. Over 60 employees took him up on the offer.

Steve Conine, co-founder of Wayfair appeared to be of the same mind when, in response to employee outcry over selling furniture to US border control detention centres, responded “we’re not a political entity. We’re not trying to take a political side.”

However, inaction is political. It facilitates and accepts the status quo.

The word ‘apolitical’ sits alongside the word ‘meritocracy,’ which was used by a CEO in a recent conversation with me to explain why pronouncements over Black Lives Matter were unnecessary in his organisation.

Both words arise from a particular view of how the world works and an organisation’s role in it. Both assume the organisation to be a separate entity, apart from society, where employees arrive ‘neutral.’

Of course, being ‘neutral’ has enabled many leaders to excuse themselves for getting on with the laser-focus attention to shareholder value – the unquestioned raison d’être of the private sector for decades.

However, now there’s a mix of factors that demand a rethink. These include:

- Millennial employees are less willing to let social and climate issues thunder onwards towards disaster.

- Technology-enabled sharing of bad behaviour and irresponsible management means you can’t ‘disappear’ your responsibility.

- A changing power dynamic is emerging as talented hard-to-find employees find themselves able to demand more from their employers.

- A significant research base enables us to conclude diverse – and included – employees make business sense even if (and precisely because) that means, inevitably, the status quo will be questioned.

The conundrum of how to respond to employees calling for action on wider social and environmental issues often falls at the feet of HR professionals to navigate. So, what options do they have? What are the consequences? And how might they seek clear commitments for action at board level and below?

More on employee activism

Pushing for progress: the workplace's role in political and social movements

HR’s role in employee activism

Workforce online activism on the rise

Social activism could turn the workplace into a ‘wokeplace’

Key findings

For six years we have been researching ‘speaking truth to power’; how habits of speaking up and silence, listening and ignoring, develop and get disrupted. Over the last year and a half, we have specifically explored employee activism. We’ve looked at what activism means to people; how employee activists experience their workplace and choose to act and the toll it takes to constantly challenge the status quo; and how organisations respond and the traps they fall into.

At the time of writing, we’ve surveyed over 1,000 employees globally (and over 8,000 as part of our overall project on speaking truth to power); interviewed around 65 activists and leaders and activist leaders (and roughly 250 overall); and facilitated hundreds of workshop discussions. Our initial findings have been published this year in our research report, The do’s

and don’ts of employee activism: how organisations respond to voices of difference.

By focusing on organisational responses to activism using the taxonomy we’ve developed, we give HR practitioners a framework to guide their conversations and actions, giving them clearer sight on the consequences of their choices.

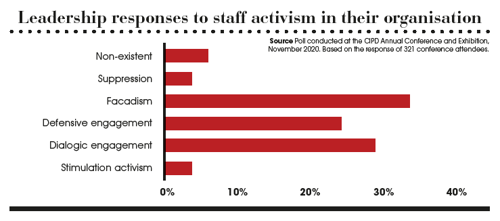

There were six common responses to activism, which apply to individual leaders as well as leadership teams – and of course HR:

Non-existent - One CEO we spoke to recently simply looked baffled when we asked him for his response.

Suppression - The example of Brian Armstrong from Coinbase, given opposite, who famously last year invited employees who wished to be at an activism-focused organisation to

move elsewhere.

Facadism - Where the leaders say one thing and do another. Statements of support for a cause are uncovered as a facade when it becomes clear that the issue is dropped the second it falls out of the limelight.

Defensive engagement - Where only what is strictly necessary is adhered to, for example gender equality is purely a tick-box exercise, enough to keep the diversity and inclusion crowd off your back.

Dialogic engagement - This is where a key shift happens with managers wanting to learn and recognising that they have a knowledge gap. There’s a genuine will to listen and jointly make decisions on social and environmental issues.

Stimulating activism – In which activists are rewarded for their activities. Outdoor apparel brand Patagonia offers employees up to two months paid leave to take part in internships at environmental organisations of their choice.

We asked 321 participants at the 2020 CIPD Annual Conference and Exhibition in November which of those categories most closely matched their organisation’s response, and their answers are depicted in the chart below.

So where would you put your personal response? And which one is most like the management response at your organisation?

Here’s the thing, if you are employed in a relatively senior role, whatever your response to the questions above is, you probably need to take it down a rung or two. What we’ve found in our research is that the more senior, the more optimistic you are about how well you know your workplace and employees; you’ll overestimate how well you’re responding. What is rich and engaging dialogic engagement to you, to others might be seen as just facadism. It is possible that HR, while hopefully being closest to employee experience, might also be somewhat optimistic.

What is clear from our results so far is that having a ‘non-existent’ or ‘suppression’ response because you have decided to ‘stay out of it’ or are hoping that your stakeholders might be duped by your facade of action, is an unsustainable path.

Megan Reitz is professor of leadership and dialogue at Hult Ashridge Executive Education and John Higgins is an independent researcher, coach, consultant, and author.

Check back tomorrow for part two of this different slant exploring how to put this research into practice.

The full piece of the above appears in the March/April 2021 print issue. Subscribe today to have all our latest articles delivered right