What’s new

Decent work is embraced by United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 8 (UN SDG8) and aims to “promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all”.

Decent work has been defined by the International Labour Organization (ILO) as summing up “the aspirations of people in their working lives", offering: a fair income; security and social protection for families; prospects for personal development and social integration; and freedom for people to express their concerns, organise and participate in decisions that affect their lives and equality

of opportunity.

Despite ongoing calls for decent work from the UN and ILO, in reality, in-work poverty is increasing in developed countries such as

the UK and US.

Are we turning back the clock on workers’ rights in the UK?

In-work poverty: All work and no pay

Employers can reduce poverty by offering flexible work

In-work poverty can be caused by low pay and limited working hours, but similarly job insecurity is caused by zero-hours contracts or other work practices that make the human resource expendable.

Many developing nations also have more of their workers in their informal economy, which leads to work precarity and exploitation as there is no formally established working agreement between employer and employee.

Inequalities are often systemic and the marginalised are undermined in their attempt to improve their lives, but recent research in Vietnam is showing how inclusive policy, levers and interventions can strive to achieve access to and participation in decent work.

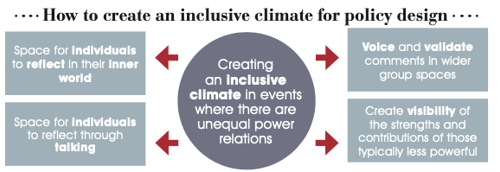

The Vietnam study used ‘appreciative inquiry’, a collaborative and strengths-based approach to development. This method was informed by the principle of collective and participatory decision-making used by the Poverty Truth Commissions (PTCs) across the UK.

The PTCs co-created meaningful and longer-term solutions and change by building relationships between those with lived experience with those in positions of influence.

Key findings

Reskilling and employment

As a fast-growing economy, Vietnam has been grappling with reskilling and employment challenges not only because of industrialisation, digitisation, regional development, but also climate change.

It is important to acknowledge that the Vietnamese government has recognised varying challenges and has been active in producing policies to improve education and training, designed to close the skills and employability gaps.

However, the mismatch between overarching government policies and the more localised or regional priorities remains problematic.

Although it could be expected that young Vietnamese would be able to find employment more easily, due to their more recent education and learned skills, this is not necessarily the case.

Employers perceive that for Vietnamese businesses to thrive in the global economy they need employees with English language and digital skills.

Certainly, it is acknowledged that the relationship between employers and universities remains weak, often resulting in a disparity between employers needs and graduate knowledge or attributes.

It is widely perceived that a higher education system that lacks practical modules does a disservice to young people and to employers.

Inclusivity

Young people from ethnic minorities have a lack of role models who have worked their way through the education system and into decent work. Therefore, there is no catalyst for change.

As their education and transferable skills do not match the level of the dominant ethnic Kinh group, they can be seen as less employable. With each ethnic group having differences of culture and language, this impacts their behaviour and the ways in which others outside of the group view them.

Employers often perceive that young ethnic minorities have a lack of interest in work, training or applying themselves. Equally, that they are only looking for jobs that they want to do.

For those young ethnic minorities who do graduate they often feel unable to be career focused. They perceive that they are not treated equally and, for example, prized tenures at government agencies are not accessible to them. They perceive that there are not enough local resources to help them find work.

While searching for work they help in the family home, and if they find employment it is likely to be a random job choice or a temporary position. Consequently, they tend to prioritise earning money, a sustainable job and staying in their hometown.

Check back tomorrow for part two of this different slant featuring more key findings and how to turn this research into reality.

If you have a pressing D&I problem you can't get to the bottom of, send in your query to be answered by our resident D&I specialist Huma Qazi in the next issue of HR magazine.

Tony Wall is a professor and research director at Chester Business School and the International Centre for Thriving at the University of Chester and Ann Hindley is a senior lecturer at Chester Business School, University of Chester.

Nga Ngo at Tay Bac University, Minh Phuong Luong, at Hanoi University and Thi Hanh Tien Ho at Phu Xuan University also contributed to this research.

This piece appears in the January/February 2022 print issue. Subscribe today to have all our latest articles delivered right to your desk.