Click here for part one of this different slant feature contextualising Meiring's research.

Key findings

My research into the factors that influence behaviour began in multinationals six years ago. Through various roles, and several interviews with management practitioners operating globally I began to devise a conceptual framework of factors grounded in psychological theory and real-world practice.

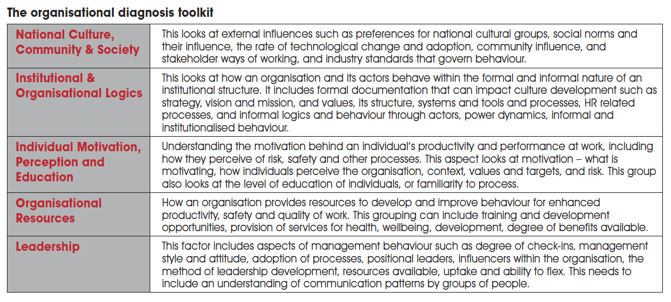

The output of the conceptual framework is an organisational diagnostic tool, The Organisational Development Model, that can be used by OD, HR, and project management professionals to build a ‘blueprint’ of the factors that are likely to influence behaviour – either through constraining behaviour or improving it.

The OD Model is based on practical, action-oriented research within multinational organisations and those with diverse populations. It focuses on the contextual variables that influence behaviour, and thus has a unique perspective on organisational development. It incorporates the latest ideas on organisational and institutional logics, and psychological theory based in motivation and cognitive function across different cultures.

There are several useful OD models that practitioners have been able to use such as Weisbord’s (1976) six-box model, the Nadler-Tushman (1977) congruence model, Tichy’s (1983) TPC framework and the Burke-Litwin model (Burke, 1992) but little work in this area has been developed in OD in recent years – a focus on dialogic processes, change management, and aspects of this work have been at the forefront of OD instead.

There is however usefulness in using diagnostic tools in understanding the scene and painting a new picture. The aim of OD models is to find a level of congruence, or equilibrium between factors, between factors and subfactors, and between the organisation and its environment, highlighting where and how resources and interventions will best be served.

Factors that can be considered in a diagnostic approach to multinational organisations, those merging, and international major project developments are highlighted in the table below.

The questions to consider when looking at these factors are:

- Are they available?

- What is their impact on individuals?

- What is their impact on other factors?

Practitioners can use focus groups and survey data to reveal the beliefs and emotions that employees at all levels are experiencing. Some of the challenges from the research looked at the stereotypes present for different populations and the impact someone perceived as ‘foreign’ can have.

It looked at availability of processes and how the English language may not be the only language predominant in the organisation. It looked at the hiring of staff from different parts of the globe, and what this meant in terms of contractual obligations and when it is appropriate to terminate contracts.

These challenges are not easy to solve but headway can be made in careful consideration of the more predominant influences that might be at play.

From research to reality

Change and organisational development is needed at the planning stage of mergers, integrations, acquisitions,

scaling business and when undertaking major projects. When this happens, change by design does not need to modify existing normative behaviour, but can implement new behaviours in a more natural, systems-based way.

It’s fundamental that HR become more strategic in its approach to people and the organisation when diverse cultures and complex environments are found. In this way, HR becomes a real strategic partner to the business.

OD tools are available to assist HR practitioners to do this – providing an understanding of the influences of behaviour that may be operating and incorporating best practices into the institutional memory of the organisation. In a very practical sense, when it comes to understanding more about the organisation, more dialogue should be involved.

Thinking about reward processes, some items worth considering when establishing a formal rewards system are:

- The attainment of rewards is not the main goal. Check to see if it bypasses the rewards afforded in the journey through a task well-done i.e. reward through delegation and conversations about the style, approach, and decisions that will need to be made.

- Treat rewards carefully. Rewards without transparency, consistency, and criteria can bring up a multitude of challenges and resistance to its appropriateness and use. Rewards confer power onto people, usually in a monetary sense, and power is relational. Decisions about power should be made with an understanding of who holds it, who is motivated by it, who is resistant to it, and how it can change behaviours (both positively and negatively).

- If the organisation is after a culture of appreciation and collaboration, couple it with conversations with people on how they already show appreciation within their teams and if a formal reward programme is necessary. Without the research into the customers of a reward programme, and its co-creation and fit, a reward program can be seen as just another initiative. If suspicion or frustration already exists around the total rewards for employees, and a formal programme is set to measure who gives or receives rewards, then it is likely to fail.

- Figure out what staff really want. If the purpose of the reward program is to motivate or retain staff, have some conversations to find out if rewards are the preferred way of doing that. There might be something else more important to sort out, like allowances, salaries, or job fit that staff will suggest they need.

Understanding the many influences of behaviour in an organisation can assist leaders and practitioners to develop a holistic understanding of what can both constrain and improve behaviour and performance.

When working internationally, with diverse populations and multiple partners to a contract, or to establishing a new organisation – these are situations that benefit from diagnostic and dialogic approaches to creating a better understanding of what works, building an organisational culture that fits, using preferences and differences to create better work practices, and to sustain better health and performance.

In enhancing your toolkit, partner with OD practitioners, or use their tools to develop more strategic approaches.

This is part two of a two-part article exploring the importance of a rewards strategy tailored to international differences.

The full article of the above is published in the November/December 2020 issue of HR magazine. Subscribe today to have all our latest articles delivered right to your desk.