Everywhere you go the same sermon seems to be preached: organisations are facing great change. So much so that the only certainty is uncertainty. And yet when I reflect on one key area – the acute shortage of HR skills in industrial relations (IR) and employee relations (ER) – I can’t help thinking nothing has really changed.

More than a decade ago I wrote an article where I highlighted the eagerness with which the Ulrich model was being adopted. My prediction then was that its rapid adoption would have serious consequences for some aspects of HR. All this time later and the model is still just as coveted, just as prized, and (perhaps more worryingly) still being rigidly adopted.

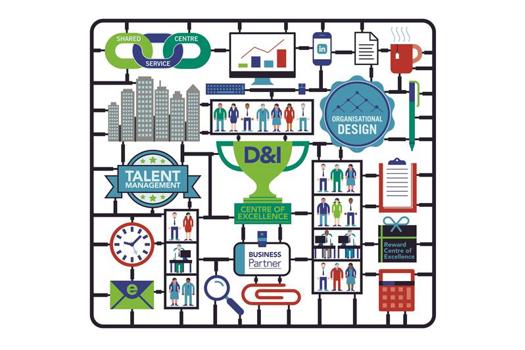

It’s easy to see why Ulrich stuck a chord; it was a way out of trouble. Almost instantly the model came to be seen as the silver bullet the strategically-struggling HR profession was desperately seeking – it became the solution to how to add value. By creating business partners (BPs) and centres of excellence, time could be freed up, transactional duties could be pushed down the line, while BPs themselves could draw on service centres for advice rather than become experts in a particular area. It all seemed too good to be true.

My contention back then was that the Ulrich model would have serious and long-lasting implications for the HR generalist – the person who hitherto had amassed valuable frontline experience in recruitment, training, reward, employee relations, organisational design, talent management and much more. These are the skills and experiences still needed for most to climb the HR career ladder. Sadly I’ve been proved right.

Ulrich falls down when it comes to IR and ER. Try putting both these important areas into shared services and it doesn’t work. Good employee relations is about establishing relationships and being on the ground listening to people. It’s about real face-to-face contact, not phoning a contact centre.

The Ulrich model destroys the process of gaining rounded HR skills. Most HRD jobs, for example, want candidates to have a full suite of HR skills. But in an Ulrich-type model that is very difficult to achieve within a reasonable amount of time.

But there are other implications too. Not only has the adoption of Ulrich meant there is a large cohort of HR professionals working today that have no ER or IR experience. But also, when organisations do want to recruit people with these skills, they’re fishing from an ever-shrinking labour pool. Our own interim practice is busy with employers wanting people, but the availability seems ever-shrinking.

ER/IR professionals that do have the requisite experience tend to stay put. And understandably so. They’ve done all the hard work; they’ve built communication pathways, gained trust, and engaged hard with the business. For the most part their employers don’t want to let them go.

The Ulrich model does have its merits. It was clever, academically-sound and built with the support of many HR professionals across the world. On paper his model should have been the passport HR has always needed to get itself to the strategic table. But with McKinsey & Company finding only recently that 60% of HR is still only involved with transactional work, the goal of freeing up time for strategic input has yet to be achieved.

To me HR leaders need to give serious consideration to the ER/IR skills shortage and what can be done to develop HR people inside of organisations. There are some great examples of this happening, but more needs to be done. The profession also needs to accept that criticising a model that has also been an amazing driving force in HR for the past 15 years is OK.

I am not advocating a return to how it was. This debate is about how we move forward. Today the application of good ER/IR skills isn’t just about dealing with unions or strikes, or threats of strikes. It’s relevant to workplace relations, employee engagement, employee advocacy and above all in achieving change in unionised and non-unionised organisations of all sizes.

So, given change is all around us, let’s not be afraid of a bit of internal change – in particular attitudinal change to accepted ways of working that might herald different, more innovative ways of thinking. No academic model is ever a panacea. We all instinctively know there is never just one version of the truth. So seek (and then do) what’s right for your business – not necessarily what Ulrich might have said a generation ago.

Andy Cook is CEO of Marshall-James, and former HRD at Gate Gourmet and former interim HRD at the British Library